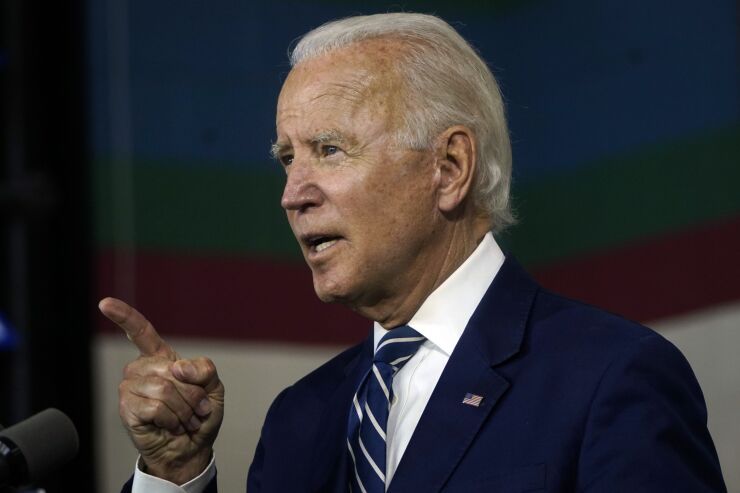

More than a half century after Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty, President Joe Biden is planning to take on the nation’s enduring challenge of inequality with a mass expansion of government spending and a revamp of the Tax Code.

The effort, which Biden will start to detail in a speech Wednesday in Pittsburgh, is already proving just as divisive among economists as it is among lawmakers. While right-leaning economists warn about damage to overall growth from higher taxes on companies and the wealthiest Americans, liberals say the “trickle-down” approach of recent decades has failed and it’s time for a new strategy.

The president’s remarks will lay out the infrastructure portion of an overall package expected to total more than $3 trillion. While social-spending programs will be outlined later in April, the administration’s drive to expand help for the poor will be visible even in infrastructure, through proposals such as the provision of safe drinking water.

“It’s important to acknowledge that we’ve seen decades of this rising economic inequality,” Heather Boushey, a member of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, said last week in an

For many, it’s not working well. The gaps between the richest Americans and the middle class, along with the lowest-income households, widened in the years before the pandemic struck — even amid the longest U.S. expansion on record. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell is among those agreeing that inequality holds the economy back, something that contributed to the overhaul in long-term monetary policy strategy he’s instituted.

Halting or reversing the trend even with major changes in policy won’t come easily or quickly, economists widely agree.

“You’re turning a supertanker, and it’s taken us a generation and half to get here,” said Brad Delong, an economics professor at the University of California at Berkeley. “But, yes, you can start to turn the supertanker.”

No single statistic captures the problem, but simple dispersions of wealth and income tell a discouraging tale:

- Average incomes for the top 5 percent of households were quadruple those of the middle fifth of Americans in 1979. That swelled to 5.7 times as much in 2007 and further to 6.6 times by 2018, U.S. Census

data compiled by the Tax Policy Center show. - The net worth of the top 10 percent of households in 1989 was 9.4 times that of the middle fifth, according to Fed data compiled by the Tax Policy Center. That

increased to 13 times by 2007 and 17 times by 2017. - The share of total income going to upper-income households — defined as double the median level —

surged to 48 percent from 29 percent from 1970 to 2018, according to the Pew Research Center. Middle-income households’ share of total earnings dropped to 43 percent from 62 percent.

Americans have long accepted some level of inequality, given the rationale that it reflects the rewards for hard work, risk-taking and ingenuity. Yet for researchers like John Friedman, an economics professor at Brown University, the problem is not just about outcomes.

“It’s not just that there’s growing inequality from an ex-post perspective, but there’s tremendous inequality of opportunity,” he said.

He points to data showing how children who display similar academic abilities at very young ages, but come from different income and racial backgrounds and varying types of neighborhoods end up with

“It’s not just about who’s smart,” Friedman said. “And there’s almost universal agreement that having your life possibilities determined by the accident of your birth is not something we’re OK with.”

But economists are in sharp disagreement on whether Biden’s economic agenda will be well-aimed at addressing inequalities. One example: Biden is expected to propose free tuition at the nation’s community colleges.

Free tuition

Glenn Hubbard, a Columbia University professor who served as chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush, has called community colleges “the logical workhorses of skill development.”

But in an interview, Hubbard said the free-tuition idea gets it “exactly backward” by subsidizing the demand for community colleges. He backs a supply-side concept of federal grants to those schools that are contingent on better graduation rates and employment outcomes after graduation.

And that’s not strictly a conservative approach. The proposal’s co-authors included Austan Goolsbee, who served as CEA chair under Democratic President Barack Obama.

There’s a wider divide over Biden’s tax policy.

Higher taxes on companies and the rich will only weaken the dynamic of wealth accumulation that drives investment, which in turn powers economic growth, conservatives argue.

“In this debate, there is a fair element of ‘We just need to punish the rich; they are rich inappropriately,’” said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the American Action Forum, a conservative research group. “With that, it’s hard to get agreement on policy.”

Liberal economists respond unapologetically, that so-called trickle-down economics — where overall economic growth lifts all boats across the income spectrum — just haven’t proved true over the last 40 years.

Spending on investment outside of housing rose an average of 3.4 percent a year from 2000 through 2019, down from 5.2 percent the prior two decades and a heady 7.2 percent in the 1960s — when tax rates were substantially higher.

Companies have the cash to grow, but with wealth and income skewed to the top, “there’s not enough customers to buy the new output,” said Josh Bivens, director of research at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute.

— With assistance from Catarina Saraiva and Vince Golle