More and more companies say they can see the future, but only through their rainbow-tinted kaleidoscopes.

For instance, Newell Brands Inc., maker of a household goods such as Sharpie markers and Rubbermaid containers, forecasts that a key measure of its income, which the company calls “normalized earnings per share,” could rise slightly to as much as $2.85 this year from $2.75 in 2017. Newell’s actual earnings, as defined by Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, or GAAP, will almost certainly plunge. Sales of its Graco strollers have been hit by the Toys “R” Us bankruptcy, a key distribution outlet, and the company is divesting some of its other brands.

Newell’s management, despite being able to forecast its favored normalized EPS metric as well as operating cash flow, says it’s unable to predict what its actual bottom line could be and even states that doing so would mislead investors. Four Wall Street analysts say Newell’s net income, as measured by GAAP, could fall to $2 a share this year.

Ford Motor Co. has a similarly limited optimistic view of its future. Earlier this year, the carmaker predicted that its company-specific accounting metric “adjusted EPS,” which excludes pension costs, restructuring expenses and other items, would fall 4.5 percent in 2018. Its actual EPS? The company said that would be too difficult to predict. Seven analysts say Ford’s net income, as measured by GAAP, will fall nearly 20 percent to $1.53 share.

Bespoke earnings measures, often called adjusted or pro forma by companies, or more derisively as earnings-before-the-bad-stuff by critics, are nothing new and seemingly everywhere. One notable recent example was office space developer WeWork Companies Inc.’s use of “community-adjusted EBITDA,” which conveniently excludes the cost of developing new office space. U.S. aluminum company Aleris International in a recent debt deal listed not only its “adjusted EBITDA,” which added $86 million to its annual earnings, but its “further adjusted EBITDA,” which tacked on an additional $36 million. Last year, toymaker Funko Inc. said in its IPO prospectus that its earnings as measured by “adjusted EBITDA” had been up 86 percent in the previous two years. Its actual income before the IPO was falling. Funko is being sued for misleading investors.

Executives and accountants defend management-adjusted earnings in part because they say they present a clearer view of a company’s operations than one-size-fits-all accounting rules. They also say they’re transparent. No investor is forced to rely on them, they say. Companies must report GAAP earnings. If they opt to also report adjusted results, the Securities and Exchange Commission requires public companies, or those that have public debt, to detail what adjustments were made. And adjusted earnings can’t be reported any more prominently than standard measures of sales and earnings.

But that’s not the case when it comes to forecasts. For forecasts, companies are allowed to use management’s preferred adjusted numbers without telling investors what they think their GAAP earnings will be or what adjustments have been made. Those adjustments are supposed to be consistent from quarter to quarter, but even that doesn’t have to be strictly followed. The SEC’s sole requirement is that companies that provide only adjusted forecasts have to state that predicting earnings based on standard accounting rules would be either too hard or too costly, which is exactly what more and more companies are doing.

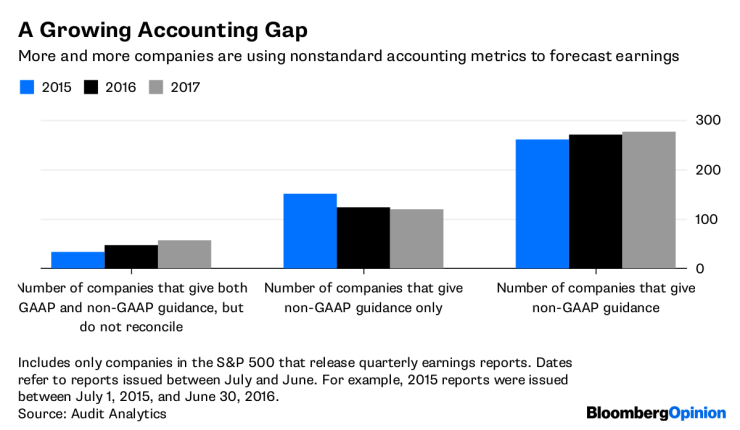

Of the companies in the S&P 500 Index, more than half, 277, now give earnings guidance based on their chosen formula, according to an analysis of financial disclosures by accounting research firm Audit Analytics prepared for Bloomberg. That’s up from 260 two years ago. Of those, more than 40 percent, or 120, provide only their bespoke earnings forecast. An additional 56 companies give both GAAP and non-GAAP forecasts but don’t detail how those two metrics compare, namely the costs, or one-time charges or gains, that are excluded to calculate the adjusted forecasts. Among the group are pharmaceutical giant Pfizer Inc., retailer Walmart Inc., both American Airlines Group Inc. and Delta Air Lines Inc., as well as beverage giants Coca-Cola Co. and PepsiCo Inc.

Most have adopted similar language in their financial disclosures and press releases to explain why it would be either impossible, or too costly, to reconcile their forecasts with standard accounting measures. Stock-based compensation is often excluded from adjusted earnings. So a number of companies say calculating it would be too impossible to predict, even though stock-based compensation is a cost you would think companies would have a handle on.

All of this can create wiggle room for companies, and possibly confusion. Johnson & Johnson’s CEO Alex Gorsky, for example, in a first-quarter earnings release in April, trumpeted “sales and EPS growth” as evidence that the company’s performance was “strong and consistent.” The problem: The company’s EPS shrunk in the quarter, down nearly 1 percent from a year earlier. Its “adjusted diluted earnings per share” did rise, up nearly 13 percent, but that was only after excluding a billion-dollar write-down of an intangible asset and more than $200 million in restructuring and acquisition costs.

There has been some pushback. In early May, the SEC sent a letter to Ford, telling the automaker that if it planned to continue forecasting “company operating cash flow” it would need to explain why its metric rose $1 billion in the quarter while the company’s official “cash flows from operating activities” fell $800 million. Ford opted to rename the figure “company adjusted operating cash flow” as well as state in future press releases that non-adjusted operating cash flow would be “difficult to quantify or predict with reasonable certainty.”

And the number of companies in the S&P 500 that detail the difference between their bespoke earnings forecasts and expected GAAP earnings is on the rise, to 101 in the past year from 75 two years ago, according to Audit Analytics.

It’s hard to believe companies can profess such mastery of the numbers that put them in the best light while claiming mystery about the rest. As happens in bull markets, though, none of this seems to matter much. Even unadjusted, profits are expected to jump an average of 20 percent in the second quarter for companies in the S&P 500, though that includes a one-time boost from the tax plan. The question is what happens when the economy turns. If companies continue to make their projections as sunny as possible, investors could react harshly when it becomes clear just how much in the clouds the forecasts have become.