Many accountants get into the profession because they enjoy balance. The numbers add up in the end and that keeps business operations running smoothly. But too many businesses are leaving money on the table because of bad financial data. The accounting profession has to take a long, hard look at what’s going on.

For many public and private companies, the ability to access capital at an opportune moment can mean the difference between success and failure. Perhaps the organization wants to expand operations, launch a new product, enter an untapped market, or plant a flag in a new location. To seize the opportunity, money either must be accessible internally or available from public markets or venture capital.

But what if it isn’t? This predicament — a market opportunity beckons but requires a fast infusion of capital — is far from uncommon for many midsize (and even larger) companies. To secure capital, the company’s financial strength, stability, governance and reputation are among the most critical factors in investors’ determinations. If one of these factors is compromised, it can directly affect the ability to secure funding.

Lately, the latter two factors — corporate governance and reputation — have been in the crosshairs of institutional investors, which is evident in the current

The need to restate the financial figures is either the result of accounting errors, noncompliance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), fraud, misrepresentation, or a simple clerical error. In 2018, restatements involving material inaccuracies in a prior year’s financial statement

Companies stuck in this quagmire experience not only the typically adverse market reaction, but they also may have a tough time raising capital. That’s just one of several findings from a recent Censuswide survey conducted for BlackLine, which polled more than 1,100 C-level executives and finance professionals.

Forty-one percent of the survey's respondents said inaccuracies in their company’s financial data, discovered after reporting their financial figures, would affect their ability to secure capital, slowing their growth prospects. Forty percent of respondents projected that it would increase their company's debt levels and 42 percent said it would result in significant reputational damage.

Since financial data is also the foundation of a company’s key performance indicators, accuracy is crucial for decision-making. Yet, an astonishing 69 percent of survey respondents believe their organizations have made significant business decisions based on inaccurate financial data. The question is why so many companies tolerate imprecise data, given the adverse business outcomes it instigates.

Deep divide

This is disconcerting news, to say the least. Equally distressing is the dismally low number of finance professionals — people like financial controllers, financial analysts, accountants and auditors preparing the financial statements and reports — who lack complete trust in the accuracy of their company’s financial data. Whereas 71 percent of C-level executives in the survey trust the numbers, only 38 percent of finance professionals feel the same way.

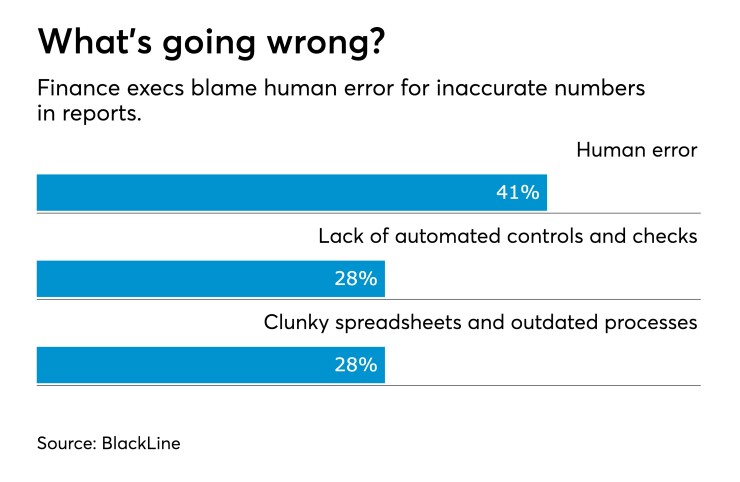

Is there anyone better to comment on the integrity of the financial figures than those in the trenches collecting, inputting and sharing this data? I don’t think so. Asked why they mistrust the accuracy of their company’s financial figures, respondents cited human error as a key factor. With so much data flooding a business from so many different systems, the risk of making a mistake while preparing financial data has skyrocketed.

Regrettably, this situation is likely to get tougher before it gets better. Total worldwide data is forecast to grow from

Cognizant of the risk of human error, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) permits an acceptable use of estimates, appraisals and judgments in organizing the financial statement. However, the agency’s new

Similarly,

Breathing a bit easier

Aside from the stock market repercussions of a restatement, inaccurate financial data sticks to a company’s reputation like glue, according to the

There is a way to vastly improve the odds of getting the numbers right — it calls for relieving finance and accounting professionals of the need to manually prepare and validate the financial statements and reports. The latter task is daunting for many companies, given the protracted lack of transparency into the origins and subsequent history of transactions to verify the numbers are correct. In fact, more than a quarter of the survey respondents (26 percent) expressed concerns about errors they knew existed, but they had no visibility into the data to alleviate these worries. Interestingly, nearly seven in ten respondents (69 percent) said a company at which they worked during their careers was compelled to restate its earnings because of unidentified data inaccuracies.

The use of automated finance and accounting software would relieve these tensions, illuminating the flow of enterprise-wide financial data to validate the accuracy of these figures in real time for accounting purposes, preserving the opportunity for the company to rapidly secure capital for business growth. With 175 zettabytes soon to be flying in over the transom, no time is better than the present to get the numbers straight.