The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board adopted new ethics and independence rules for auditors that place clear limits on the ability of accounting firms to offer tax services to their audit clients.

Although the new restrictions stop well short of an all-out ban on the provision of tax services by auditors - a course advocated by some critics of the profession - they do make it clear that offering aggressive tax shelter schemes to audit clients will not be tolerated.

Under the recent rules approved by the board, an audit firm will not be considered independent if it offers its audit clients tax services "related to marketing, planning or opining in favor of a tax treatment on a transaction that is based on an aggressive interpretation of applicable tax laws and regulations."

The restrictions are aimed at curbing auditor involvement in "egregious tax dodges that impair independence and undermine public confidence in auditor integrity," PCAOB board member Daniel L. Goelzer said in voting to establish the new rules.

The standards adopted by the board further prohibit auditors from offering tax services to clients on a contingent-fee basis, and from providing tax services to certain members of management who serve in financial reporting oversight roles at an audit client.

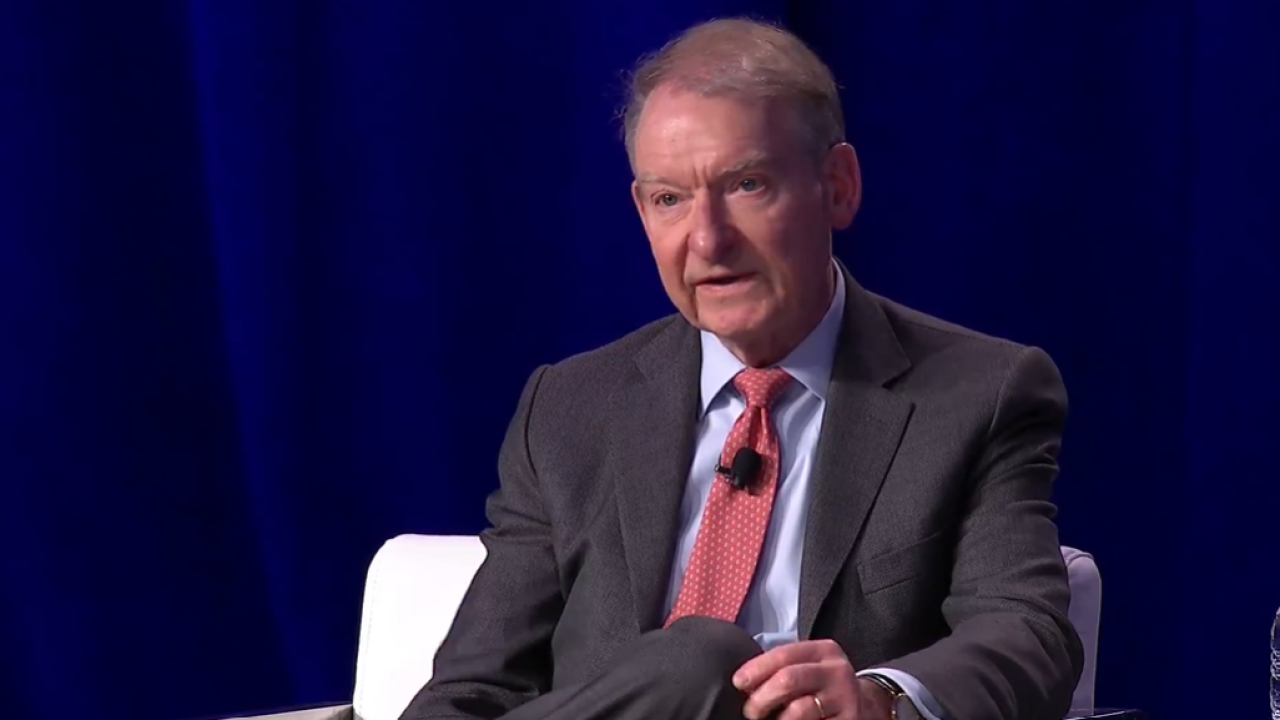

PCAOB Chairman William J. McDonough described the new ethical guideline on auditor tax service as "right for the investing public, because it will keep the auditors of public companies out of the aggressive tax work that has so damaged the public's confidence."

At the same time, he said, "It's right for the auditing profession, too, because these rules draw clear lines to distinguish inappropriate services that impair auditor independence from permissible services that are not detrimental."

Although some public interest and investor groups had urged the board to adopt a far more restrictive approach to auditor tax service, McDonough said that an all-out ban on tax work by audit firms would have been overkill.

"We could have approached the topic with a broader brush, by prohibiting tax services entirely," he said during a public meeting where the standards were announced. "I do not think that is necessary, nor would it have been appropriate."

Tough enough?

At least one board member suggested that additional tightening of the restraints on auditors may be warranted.

Rather than merely prohibiting the offering of individual tax services to certain financial executives at audit clients, some commentors had urged the PCAOB to prohibit such services to all directors, board member Kayla Gillan noted. Others, meanwhile, called for disclosures of tax services provided to all members of a client's audit committee.

"If actual practice does not conform to what we believe should be best practice, I as one board member would support re-opening this issue for further rulemaking," she said.

In seeking pre-approval from an audit committee to provide a permissible tax service, the auditing firm - if registered with the oversight board - must describe in writing the scope of service, the fee structure and any compensation agreement or referral agreement between the accounting firm and any person other than the audit client with regard to promoting, marketing or recommending the transaction.

In addition to the guidelines on tax services, the PCAOB also approved a separate ethics rule codifying the principle that persons associated with a registered public accounting firm should not cause their firm to violate relevant laws, rules or professional standards.

In response to concerns raised by the profession, however, the board agreed to modify their original plan to replace language that used a "state of mind" standard for determining ethical breaches by accountants.

Under that proposal, accountants would have been subject to ethical sanctions if they "knew or should have known that their conduct would contribute to a violation" by the firm, PCAOB chief auditor Douglas Carmichael explained.

Because of the difficulty of enforcing such a "state of mind" requirement in view of the complex regulatory requirements facing accountants, he said that the final rule was changed to assign blame only if the accountant "knew or was reckless in not knowing" that their conduct would facilitate a violation.

Carmichael also noted that the final rule was further tweaked to explain that in order for an ethics infraction to occur, the accountant's "act or omission must directly and substantially contribute to the firm's violation."

During the same meeting, the PCAOB also gave the thumbs-up to the new Auditing Standard No. 4, establishing ground rules governing whether a previously reported material weakness in internal control continues to exist as of a date specified by management.

Under that new standard, public companies will be allowed - but not required - to obtain an auditor's attestation that previously reported material weaknesses no longer exist - an option that McDonough said would "provide the investing public with added confidence" in the financial reporting of these companies.

Stressing that this attestation option will be "entirely voluntary" for companies, the chairman noted, "There are a number of other ways that public companies can complete the communication to investors that they begin when they disclose a material weakness."

Board member Goelzer added that the PCAOB does not anticipate that auditor attestations will be used so extensively that they will drive up audit costs.

The new rules must now be approved by the Securities and Exchange Commission before they become official.